“As a physician leader, I never want others to learn how to lead the way I did: by being thrown into the cauldron of a leadership position with little preparation, understanding, evidence, and application.” As designers of physician leadership development programs, we heard this lament so often it became the robust fuel that led us to design a physician leadership development program that was not only strategic and operational, but also user-friendly and fun.

“As a physician leader, I never want others to learn how to lead the way I did: by being thrown into the cauldron of a leadership position with little preparation, understanding, evidence, and application.”

As designers of physician leadership development programs, we heard this lament so often it became the robust fuel that led us to design a physician leadership development program that was not only strategic and operational, but also user-friendly and fun.

For our large national healthcare system client, we engaged both cutting-edge and seminal research, as well as state-of-the-art-and-science practices. The primary building blocks we used to make physician learning and application as effective as possible were:

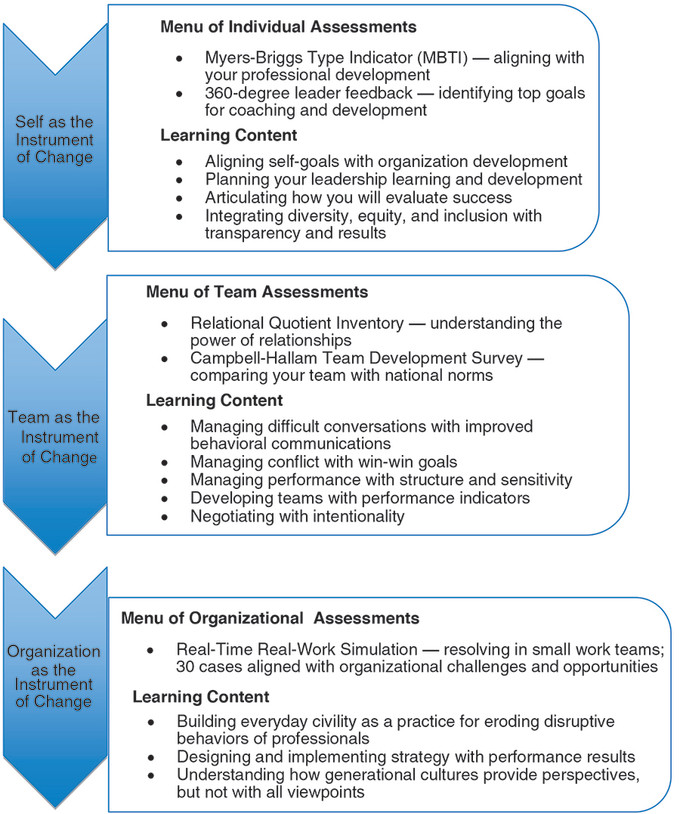

From these building blocks, we helped our client envision three instruments of physician leadership change (self, team, and organizational) for the two primary work groups: chiefs of professional services and heads of medical departments.

Within these three domains, we identified the general learning content and the specific modules associated with this content (see Figure 1) through our client’s extensive needs assessment process. We used this needs assessment to align the content with the most cutting-edge and evidence-based research.

Figure 1. The overall plan of instruments of change, content, and methods

Physicians have been educated primarily in a didactic mode. This is not the optimal way to teach and learn! Research on effective leadership demonstrates that when the pedagogy incorporates three contexts — one’s experiences, a variety of teaching approaches, and assessment — the application of learning to the field environment increases.

We facilitated seven 1½-day workshop modules over 14 months. Our strategy of action learning enabled physician leaders to bring their core challenges and opportunities to “class.” This is the fuel that develops critical insights and the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral contexts of learning and application.

The settings for this learning and action included:

Rather than allowing subject areas to drive the content, we designed the content around nine core questions that emanated from the needs assessment. Participants appreciated this “fresh” approach to learning: answering their key questions. Below are the core questions and how they are woven into the content.

It was important to have an advisory board that consisted of key physician leader stakeholders who collaboratively designed the entire program with the facilitators. In addition, this advisory board supported formative changes every quarter, so the program addressed all challenges and opportunities. With the advisory board, we integrated the needs assessment previously conducted, the evidence-based literature, our experiences based on benchmarked work with physician leaders, and methods to develop insights that translate into successful practice.

We discovered that without senior leadership’s consistent interest, support, and suggestions throughout the physician leadership development program, this program would not have been nearly as successful. And this was not just lip service; they provided time, resources, funding, and outstanding participants to make this program hum to the tune of success.

We engaged two unique types of evaluation methods to assess the learning and application throughout the program using the retrospective evaluation and the capstone real-time work simulation.

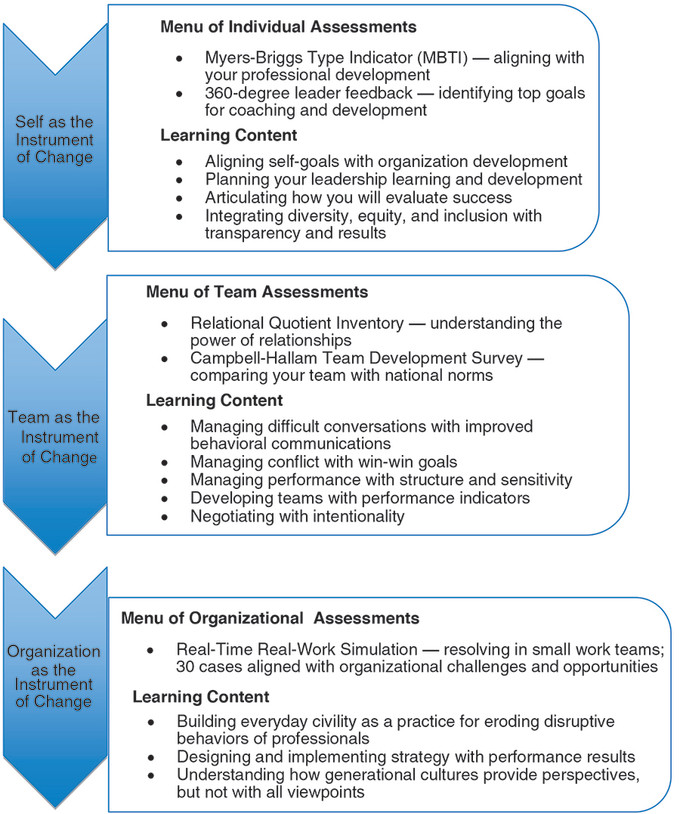

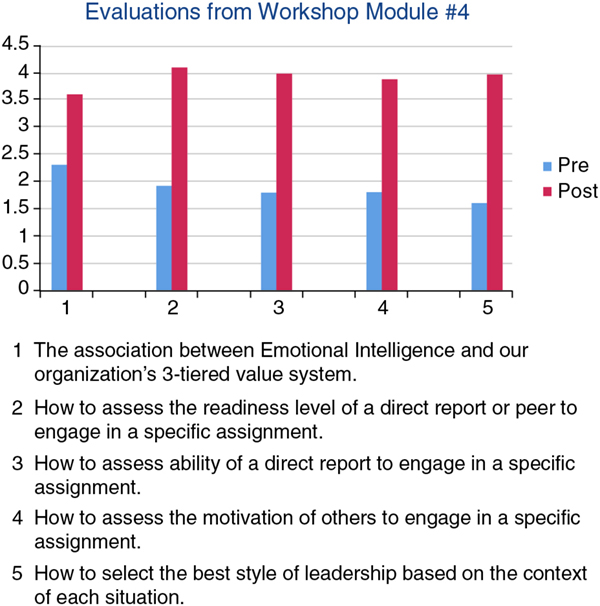

The retrospective evaluation is based on the research of Preziosi and Legg,(10) who demonstrated that in traditional pre-post assessments of learning, participants often don’t know how much they don’t know — until after they have completed their training. Therefore, after each 1½-day workshop module, we asked participants to rate their learning pre- and post- at the “post” stage in a retrospective kind of way. Figure 2 provides a rich example of this module.

Figure 2. A sample retrospective evaluation

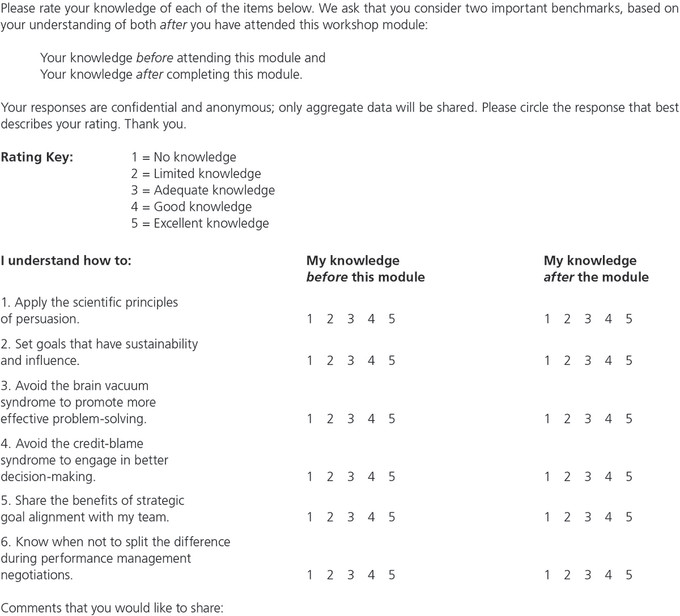

This retrospective evaluation is a method that almost 100% of our clients find appealing, user-friendly, and most meaningful. Figure 3 demonstrates results from one of the modules.

Figure 3. Retrospective evaluation results from one of the workshop modules

The second aspect of uniqueness here was that we shared the results at the beginning of each new module approximately 45 days later. This reinforced their learning and, more importantly, provided a vehicle for discussion. We recall quite vividly that participants shared not only their successes in engaging this learning over the previous 45 days, but also the obstacles they experienced in trying to apply the content. These conversations about the obstacles experienced provided further fuel for team learning and application.

The capstone real-time work simulation further cemented the learning and application by engaging the content from the entire 14-month program into a day-long session. Here, participants gathered in workshop teams of four to collectively problem-solve 35 case scenarios designed to mimic the real work they were doing as physician leaders.

Because of the complex nature of the scenarios, none had just one resolution to the case dilemmas. Instead, we identified from the evidence-based literature, the most effective ways each dilemma could be resolved. After each of the teams identified solutions to each case scenario, we then shared what experts identified as top solutions. Comparing their paths to resolution with the experts was profound to say the least. Many participants wanted to share this exercise with their own teams.

Beyond these retrospective and real-time evaluations of learning, what delighted leaders of participants in the program was that participants engaged them early on, asking for their help and guidance, rather than waiting when issues became significant challenges. Leaders discovered that these early interventions often turned these challenges into opportunities for both professional growth and organization development.

We discovered the power of teaching physician leaders how to extend their reach with this learning-to-learn model. Through content and exercises that promoted their application and using this application to teach others, they learned how to do it better.

Think of it this way: When we teach someone something, we often enhance our own abilities and applications. That is precisely what happened in this physician leadership development program. They reported being significantly better leaders when encouraged to be transparent about what they were learning and applying. So, we encouraged all physician leaders to teach others what they were learning and experiencing from the physician leadership program.

We created a safe and confidential environment for the participants, allowing them to share both positive and negative experiences based on observations of the behaviors and actions of physician leaders with whom they had interacted.

A significant learning was what “not to do” as a result of the negative experiences the attendees had observed among some of their physician leaders. Some examples of what they observed included leaders shutting down those with different viewpoints, using coercion to obtain buy-in and results, and an inability to share their vision, especially the reason change was necessary. Positive experiences and learnings included being transparent at team meetings, sharing a new strategy that was just learned, and applying practices now, and welcoming feedback from those they lead.

This physician leadership development program resulted in successful performance practices that were evidence-based and extended throughout the organization by the physician leaders themselves. They engaged the mantra: To be a leader is to teach. If you’re not teaching, you’re not leading!

The authors wish to thank Dr. Elizabeth Holloway for her engagement in this program.